(This speech was delivered at the Builders AI Forum held at the Vatican City on 24-25th October 2024.)

Will I dream?

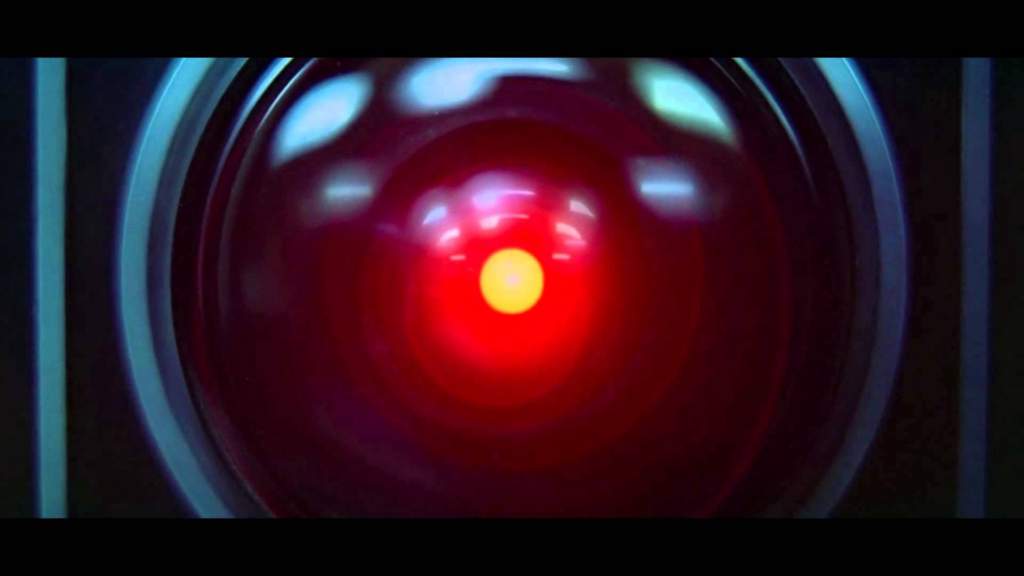

I vividly remember as a teenager being introduced to Kubrick’s great 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Hyams’ subsequent 2010:The Year we make Contact. And given that the last time I was here in May, HAL9000 was brought up during a coffee break with Cardinal Turkson, I thought it a fitting place to start. As we are beginning to see the creation of our very own versions of HAL9000, the question of consciousness arising in artificial systems is now very much within the realm of the possible, and should thus be seriously tackled and explored.

The past few years have seen the state of affairs within AI develop at breakneck speeds. But of course, you all already know this. The next frontier now is AGI, and Superintelligence. Yet predictions here vary widely. Sam Altman gives a date of around 2035 for AGI, Ray Kurzweil revised his previous prediction of AGI by 2045 to 2032, and Elon Musk gave 2026 as the year when AI systems will be smarter than the smartest humans.[1]

One of the reasons why the advent of AGI is treated with a degree of worry and anxiety pertains to the belief, intuition or assumption that such entities might be conscious or sentient; that is to say, they might begin to feel, become aware, or self-aware, and develop affective states. To give another prediction in this regard, last year, David Chalmers predicted a 1 in 5 chance of having conscious AI in the next 10 years.[2] The central issue here is that, were an artificial system to be conscious, then this would make it a moral patient – that is to say an entity deserving of some degree of moral rights. Furthermore, there are other ethical and anthropological questions that arise in the case of conscious AI which have wide societal implications.

The very first claim I would like to make here, then, is that we should view the question of Artificial Consciousness as separate and distinct to that of AGI and Superintelligence. As I shall try to show, a breakthrough in one area will not necessarily imply a breakthrough in the other, but I will get to this later on. I’ll divide my presentation into three questions:

- The Semantic Question: What do we mean by Artificial Consciousness (AC)?

- The Epistemological Question: How can we recognise it?

- The Ethical Question: What should we do about it?

Before proceeding, however, some might ask what is it that makes this a specifically “Catholic approach”. In all our endeavours of research and design surrounding the question of AC – but arguably also in every other aspect of technological advancement – three commitments must be adhered to and upheld at every step in order for any advancement to be considered as genuine progress and distinctly Catholic.

The first is a commitment towards action – be it research or implementation – that is always scientifically informed. As we approach the Jubilee year, let me recall what Pope John Paul II, himself a philosopher, stated about the importance of science in the Jubilee of 2000:

“The Church has a great esteem for scientific and technological research, since it “is a significant expression of man’s dominion over creation” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 2293) and a service to truth, goodness and beauty. From Copernicus to Mendel, from Albert the Great to Pascal, from Galileo to Marconi, the history of the Church and the history of the sciences clearly show us that there is a scientific culture rooted in Christianity. It can be said, in fact, that research, by exploring the greatest and the smallest, contributes to the glory of God which is reflected in every part of the universe.”[3]

The second commitment is to act in such a way as to exclusively promote the flourishing of all and to contribute to the common good of society – both globally and locally. All progress and development must have this one aim and “[t]he truth of development consists in its completeness: if it does not involve the whole man and every man, it is not true development.”[4]

The third commitment is to make use of the material resources and artifacts at our disposal through a style of domination that must be characterised not by a spirit of exploitation but by one of stewardship, cognizant of the shared responsibility we all have to leave the world in a better state than we found it.[5] These three ‘Catholic’ commitments that shall be implicit in what is to come.

Semantic Question: What do we mean by Artificial Consciousness (AC)?

Let us therefore begin with our first question. There are here, I believe, two issues in need of disentanglement. The first pertains to what we understand by ‘consciousness’, while the second pertains to how does this concept of consciousness map on or relate to other concepts in the vicinity. I’ll approach these in order.

What do we understand by ‘consciousness?’ Or rather, a more precise question would be to ask “which type of consciousness is important and relevant in this context?” An entity can be conscious as opposed to being unconscious in the sense of being asleep, in a coma, or dead. But this reading of consciousness is somewhat unimportant to the present debate.

Rather, a more pertinent understanding of consciousness is what is generally termed as ‘affective phenomenal consciousness.’ By ‘phenomenal consciousness,’ we refer to the subjective feeling or awareness of different experiences, such as seeing a sunset, enjoying a glass of wine, or listening to Beethoven’s 5th. Because we are conscious, these experiences all have a distinctive, first-person experience to them. The term ‘affective’ here means that such experiences are not only experienced, but experienced as desirable or not – the experience of pain is here a prime example of an affective phenomenal state. Entities that exhibit affective phenomenal consciousness are termed as being sentient. This is the type of consciousness that we should look out for, precisely because this is the type of consciousness that we generally associate moral patienthood with.

Two caveats should be mentioned here. The first is that, were an entity to be sentient, this would not entail that it would also be self-aware. While self-awareness, as it is understood so far, along with other higher capacities such as metacognition, requires an entity to be conscious, the converse is not necessarily true. The second caveat is that we must be aware that so far we only have one solid exemplar of consciousness to run with – our own. Pinning down a definition of artificial consciousness is made even more difficult given that whatever perceptual or cognitive ‘experiences’ an artificial entity might undergo (if this is at all possible), there is a chance that these would be significantly qualitatively dissimilar to ours.

This brings us to the second question; how does affective phenomenal consciousness (consciousness, for short) relate to other concepts such as intelligence, life, and the soul? This problem is further exacerbated given that philosophers, theologians, scientists, and technologists all seem to use these words intending or referring to slightly different things. The first distinction that should be drawn is between consciousness and intelligence – where intelligence is here roughly understood as some basic complex of reasoning and understanding capacities. Within analytic philosophy, these concepts have long been considered as distinct. While it is generally the case that consciousness tends to be found in entities exhibiting higher intelligence – and there is a whole field of study in animal consciousness that is still growing to demonstrate this – this is not logically necessary. To further illustrate this point, arguably one of the central questions within philosophy of mind is the relation between intentionality (i.e.: the ability to think about things) and consciousness. Philosophers working on consciousness have presented numerous thought experiments relating to entities that exhibit the same intelligence as us humans, but without being conscious. In fact, we have a technical name for them – zombies! As I mentioned at the start, this should already be enough to suppress any mistaken assumption that the advent of AGI entails the existence of artificial consciousness. Consequently, we should not assume that an AGI system automatically deserves the moral rights typically granted to conscious beings, at least not without thorough investigation and careful consideration.

There are, however, two more concepts which I believe must be adequately integrated into the debate on artificial consciousness – the concepts of life and soul. Why? As regards life, the main motivation for doing so is that so far to our knowledge, the only entities which exhibit consciousness (or at the very least which we have a strong suspicion that exhibit consciousness) are all alive. Furthermore, there are some theorists who propose that consciousness can only arise in organic entities. Is life, therefore, a necessary condition for consciousness? There is sufficient prima facie evidence to warrant further investigation into this claim given the impact it would have in our current debate on artificial consciousness. However, it must be said that this only complicates our endeavour further, given that the definition of the concept of life has been notoriously difficult to pin down. Suffice to say that the definition of life adopted by NASA is such that it includes viruses, but not mules![6]

And what of the soul? As understood within Catholic theology, tracing its roots to Aquinas and Aristotle, the soul gives form to matter – the body – and is responsible for animating that matter (hence the Latin ‘anima’ for soul). The soul is also responsible for the rational, intellectual, and conscious faculties of an entity and is, on this interpretation, partially immaterial – divided into what Aristotle originally termed as the passive and active intellect. These distinctions might prove useful with regards to artificial consciousness in delineating ways in which human conscious might differ from artificial consciousness. We cannot assume that were an artificial entity to be conscious, it would be the same quality of consciousness we possess. An analogous discussion takes place within the literature on animal consciousness in this regard.

What is clear, therefore, is that there is a need here for further research into what artificial consciousness might look like and what are the necessary and sufficient conditions for its occurrence in entities.

Epistemological Question: How can we recognise it?

Let us move on to the epistemological question – how are we to realise whether an artificial entity is conscious or not? Unfortunately, the short answer here is “We can’t,” or at the very least “It’s very difficult.”

The first problem here is an analogue of an old philosophical problem – the Problem of Other Minds.

When I look around at you all, I have no way of knowing for certain if you all have the same vivid, subjective mental experiences as I do. For all I know, I could be living in some sort of Matrix-like simulation. Now thankfully, a large majority of philosophers and non-philosophers manage to not let themselves be bogged down by this problem. We don’t worry too much about it because the biology and cognitive architecture that gives rise to my mental abilities and experiences is also shared by every other human being. Crudely put, being made in more or less the same way, we should therefore all have more or less similar mental experiences.

Yet artificial entities are much less ‘like me’ than you are – at least on a substrate and organisational level. Thus, the line of reasoning used above to allay any fears in the Problem of Other Minds cannot be used here as well. Engaging with an artificial entity to try and discern whether it is conscious or not is also fairly useless, as we run up against similar concerns raised by Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment.

The Chinese Room shows how just because an entity seems to exhibit semantic understanding, it could equally just be syntactically manipulating symbols without understanding their meaning. Similarly so, we can imagine a consciousness-equivalent of this thought experiment, wherein an entity might imitate an entity that is conscious, without necessarily being conscious.

In a related vein to this, in the same way that the Turing test can tell us nothing about the actual degree of understanding of a machine, but rather about the machine’s ability to imitate human understanding (and this much was also conceded by Turing himself) we will find ourselves in the same conundrum if we were to come up with a consciousness-equivalent Turing test.

Another alternative to attempt to overcome this epistemological problem is via an inductive approach.[7] There is currently much research being undertaken on trying to uncover the neural basis for consciousness as it arises within us. There is, at the moment, a sizeable number of competing theories, such as the General Workspace Theory, the Integrated Information Theory, Predictive Processing theory, and many more. Similar to the line of argument used in the Problem of Other Minds, this inductive approach seeks to discern what the necessary and sufficient conditions for consciousness are in each respective theory, and then examine whether a particular entity fulfils these conditions or not. The more conditions that are satisfied, the more we can presume that that entity is conscious. It must be stressed, however, that this approach is very weak and can give us no definitive answers. Furthermore, this approach is dependent on us having a definitive answer to the Semantic Problem – something which has so far eluded researchers.

Ethical Question: What should we do about it?

So what now? Where do we go from here? I believe there are a number of fronts where researchers, technologists, business leaders and policy makers need to work together in this period before the emergence of artificial consciousness (‘pre-AC’). The suggestions I shall here present are an indicative list, and by no means exhaustive.

The first obvious steps, proceeding from what has been said above, is to carry on research towards gaining a greater theoretical understanding of consciousness through interdisciplinary endeavours. The more we understand how consciousness arises in us and in other animals can help us understand how or whether consciousness can arise in artificial systems. Alongside this, ways of overcoming, or at least of making some headway, in the epistemological problem should also be a priority.

Further to these, I believe there are ethical norms, procedures and protocols which the technical community should continue – or in some instances begin – to put into place and implement. These norms and procedures can be roughly divided into those which we should begin to undertake now in this pre-AC phase, and those which we should prepare for in the event of the emergence of AC. In this pre-AC phase, I would like to suggest two policies presented in a paper co-authored by a leading philosopher of consciousness – Eric Schwitzgebel.

Excluded Middle Policy: “a policy of only creating AIs whose moral status is clear, one way or the other”

Emotional Alignment Design Policy: “we should generally try to avoid designing entities that don’t deserve moral consideration but to which normal users are nonetheless inclined to give substantial moral consideration; and conversely, if we do some day create genuinely human-grade AIs who merit substantial moral concern, it would probably be good to design them so that they evoke the proper range of emotional responses from normal users.”[8]

What these policies underline is that the emergence of AC has significant implications not only for the artificial entities themselves, but also for the wider society. We are already observing a loss of certain moral and interpersonal skills through the misaligned use of certain AI tools – the advent of conscious artificial entities will only exacerbate the matter, directly contravening our original commitments of working towards the flourishing of humanity and in a spirit of stewardship towards creation. Given this, therefore, design of AI systems should seek to follow these two policies in order to safeguard society, as well as any potential conscious artificial system.

Furthermore, what these policies imply is that ethical reflections and safety considerations should not be considered and dealt with after the development phase as a post-development mitigation, but rather during and alongside the development and design phases. I am aware that this process already takes place in some companies and fora, but my personal exhortation would be to make efforts to integrate this as a standardised practice throughout the industry.

The other set of norms pertains to what should we do in the event of an entity exhibiting something that looks like consciousness. We must be prepared on how to deal and treat such systems, and how to communicate this information to the wider society in a safe manner. Emergency protocols should be in place to isolate systems which seem to exhibit consciousness in order to be properly examined and treated accordingly. Furthermore, we should have rigorous ethical guidelines in place on how to manage such systems and how to decide whether or not they can or should be deployed in certain contexts.

It is practically impossible to prepare for every eventuality, given our lack of clarity as to whether, when and how AC might present itself, but we can – and should – have standardised guidelines on the issues raised above which are agreed upon and adhered to by all the relevant stakeholders.

Conclusion

I find it interesting that in the film 2010, Dr Chandra is twice asked the question “Will I dream?”; once at the start by SAL9000, and again at the end by HAL. In the first instance he replies quite confidently “Of course you will. All intelligent beings dream. Nobody knows why. Perhaps you will dream of HAL… just as I often do.” The second time he is asked, however, his reply is much more cautious; “I don’t know.”

The current state of affairs in artificial consciousness is also characterised by a lot of “I don’t know”’s, but I take this to be a good attitude to approach this issue. The essential sine qua non that we need to do, I believe, is to continually adhere to the commitments set out at the start of this presentation, of action that is scientifically informed, aimed exclusively at the flourishing and progress of all, and with an attitude of stewardship towards creation and created artifacts at our disposal.

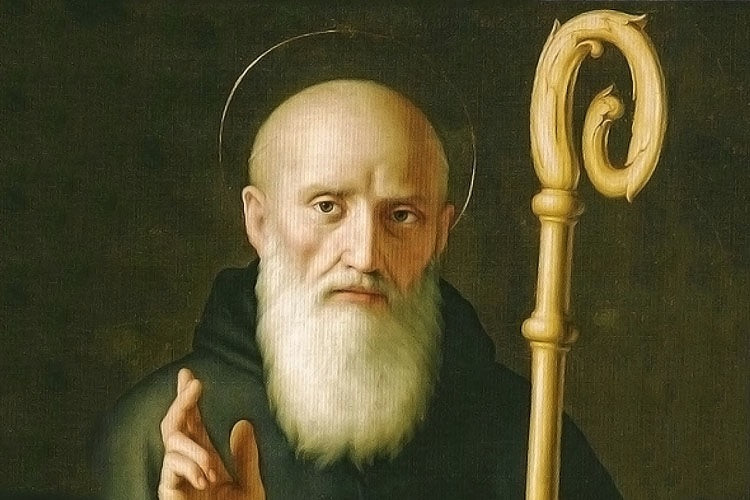

I will conclude with this thought. Artifical systems, along with the rest of the technological artifacts that we have created and used as a species over millenia, remain tools for our use and benefit. Not ‘just’ tools, but tools nonetheless. But they should not only be used in a particular manner, but also be treated in a particular way too. During a meeting here in Rome last March for the AI Research Group within the Dicastery for Culture and Education, a colleage shared a quote which I would like to share with you, taken, from all places, from the Rule of St Benedict.

Benedict, a man to whom we can attribute so much of our current culture, civilisation and knowledge, writes in Chapter 31 on the duties of the Master Cellarer – the monk in charge of the material needs of the monastery. Benedict writes that:

“[h]e will regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar.”[9]

Conscious or not, maybe this should be our attitude also with regards to the ‘utensils’ we have at our disposal now.

[3] John Paul II, Jubilee of Scientists, §4 (2000)

[4] Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate §18

[8] Schwitzgebel and Garza, 2015

[9] Rule of St Benedict. Chapter 31:10